Whether it’s due to stress, lack of sleep, or the result of a few glasses of wine, there are many reasons you may experience a…

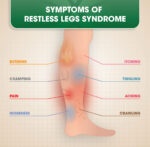

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) is a neurological disorder causing uncomfortable sensations and an uncontrollable urge to move the legs, especially during rest or at night.…

Gabapentin is often prescribed to treat Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), particularly in cases where other medications might not be suitable or effective. Restless Legs Syndrome…

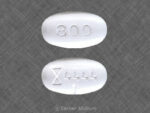

Gabapentin, also known by the brand name Neurontin, is a prescription painkiller belonging to its own drug class, Gabapentinoids. It is considered an anti-convulsant, and…

This medicine is known as gabapentin. It is available as a prescription only medicine and is commonly used for Alcohol Withdrawal, Anxiety, Benign Essential Tremor,…

Morphine is a potent opioid used primarily for pain management but has a significant potential for abuse and addiction. Here are some key statistics and…

Natural and Semi-Synthetic Opioids: A Detailed Overview Opioids are a class of drugs that are used primarily for pain relief (analgesia). They are divided into…

Semi-synthetic opioids are chemically modified derivatives of natural opioids, typically morphine or thebaine. They are designed to improve efficacy, potency, or bioavailability, or to reduce…

Natural opioids are alkaloids that are directly extracted from the opium poppy plant (Papaver somniferum). The primary natural opioids are known as opiates, which include:…

Opioid medications are a class of drugs primarily used to manage pain by binding to opioid receptors in the brain, spinal cord, and other areas…

Tramadol looks like a round or oblong pill that is white, orange, yellow, or red in color. Both brand name and generic formulations of tramadol…

Codeine works as an opioid analgesic and antitussive (cough suppressant), affecting both pain and cough pathways in the body. Codeine is from a group of…

Medications containing codeine are often used to manage pain or suppress coughing. They come in different formulations, usually combined with other ingredients like acetaminophen, aspirin,…

In the United States, hydrocodone is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, which means it has a high potential…

Hydrocodone is commonly prescribed in combination with other medications for pain relief or cough suppression. It is available in various brand-name and generic medications, usually…

Preventing hydrocodone abuse requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both individual behaviors and systemic factors related to opioid prescriptions, education, and support. Below are key…

Hydrocodone overdose is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical intervention. The risk of overdose is particularly high when hydrocodone is combined with other substances…

Hydrocodone abuse is a significant public health issue due to the drug’s addictive potential and its widespread use as a prescription pain reliever. Hydrocodone is…

Hydrocodone dependence and abuse are serious issues due to the drug’s potent opioid properties, which can lead to physical dependence, addiction, and overdose if misused.…

Back pain is a common condition that can be caused by a variety of factors, including muscle strain, disc degeneration, arthritis, and nerve compression. The…

The treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) focuses on reducing inflammation, relieving pain, and slowing the progression of the disease. Below is a detailed list of…

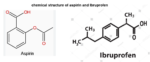

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used to treat a variety of pain and inflammation conditions. They are effective because they block the production of…

Although taking expired ibuprofen is not recommended by the manufacturer, the actual shelf-life is likely to be longer than that indicated by the expiry date,…

Even though aspirin and Ibuprofen are both NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and work similarly, that is by blocking the body’s production of prostaglandins which relieves…

Yes, it is safe for most people to take tramadol with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or aspirin if they are old enough (aspirin is not recommended for children less than 16 years and…